The Perfect Book for July 4th

by Judy Helfand

An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz sat on my bookshelf for months. I’d picked it up because I admired the author, having read her memoir Red Dirt: Growing Up Oakie, which seriously grappled with whiteness. When I finally took the history off the shelf and began reading, I couldn’t put it down. Here was the story of indigenous people in all their variety from before Europeans arrived in North America through the resistance to the conquering and colonization that followed. In parallel Dunbar-Ortiz provided a history of the tactics, social policies, and campaigns that drove the colonizing forces in their efforts to claim the land that became the United States.

An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States by Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz sat on my bookshelf for months. I’d picked it up because I admired the author, having read her memoir Red Dirt: Growing Up Oakie, which seriously grappled with whiteness. When I finally took the history off the shelf and began reading, I couldn’t put it down. Here was the story of indigenous people in all their variety from before Europeans arrived in North America through the resistance to the conquering and colonization that followed. In parallel Dunbar-Ortiz provided a history of the tactics, social policies, and campaigns that drove the colonizing forces in their efforts to claim the land that became the United States.

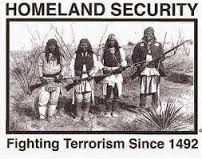

Upon European arrival, there were complex, interdependent, culturally sophisticated agricultural societies all over the Americas, including what became the U.S. These societies had various types of governments and leadership. An Indigenous Peoples’ History makes clear the indigenous peoples’ strategic responses to encroachment on their territory and threat to their way of life. Most indigenous cultures had recognized methods of waging war, some fairly ritualized. They were unprepared for the type of war developed and waged by the colonists and then the U.S. government, warfare we now refer to as “counterinsurgency.” Dunbar-Ortiz documents the refinement of a way of war that has been used since by the U.S. overseas. Well coordinated campaigns focused on destroying food sources and stores of food, burning dwellings, and killing vulnerable non-combatants, turning them into refugees. This approach to war aimed for unconditional surrender. The U.S. government declared a goal of erasure and total destruction of Indian people and utilized the military as well as unofficial “Indian killers” to accomplish this goal.

Native people commented consistently on the greed, especially the desire for money, they witnessed in European settler colonists. Europeans saw everything as commodity – people (slaves); land (real estate); plants, animals, and minerals (resources). This was in stark contrast to the indigenous view that generally saw humans as part of the whole and aiming to live in harmony with other aspects of creation. Europeans being so (de)formed by their own worldview often could not even see indigenous peoples as civilized, with economic, agricultural, political, religious, and social systems of their own.

The stories the colonizers told themselves to explain their development of the United States are the stories still taught to American children: the stories of intrepid pioneers and uncivilized savages; stories of battles by U.S. cavalry that were actually massacres of indigenous elders, women, and children; stories about how native peoples were not “using” the land. There are stories by omission – nothing about the richness of indigenous cultures nor their resistance; nothing about the calculated and strategic efforts by US government and European settlers to drive out the land’s original inhabitants and destroy their cultures. And there are stories the ancestors of those settler colonialists are creating today to counter the continued resistance of Indian nations.

Dunbar-Ortiz covers over 500 years of history of the indigenous people in the United States with historic details and insightful analysis that links the past to the present, asking important questions about U.S. Empire and the need to address militarism. She asks how US society can come to terms with its past and take responsibility for the society of today, which is a product of that past. I highly recommend An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States as a starting place to acknowledge the roots of the U.S. and find inspiration for taking the steps necessary to begin undoing the damage.

Leave a Reply